Two Sentence Styles You Might Be Overusing, by Jude Hopkins, 7/18/23

- J Hopkins

- Jul 18, 2023

- 5 min read

Are you inadvertently boring your readers because of your reliance on mainly two sentence styles? Those styles are the compound sentence and the loose sentence (also known as the cumulative sentence).

Here’s an example of a compound sentence: “Writers like compound sentences, and they use them a lot.”

We can see the two independent clauses (two sentences that can stand alone) joined by a comma and a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so, easily remembered by the acronym FANBOYS).

Here’s a cumulative or loose sentence: “Writers like loose sentences, a style that allows them to keep adding phrases, giving them the freedom to keep writing without stopping, providing them the illusion of endlessness.”

Let’s face it: Writers like to write but don’t always want to edit and polish their pieces, relying on the ephemeral muse instead, which is why these two sentence styles in particular are so popular. They adapt to creative minds that like to keep adding information without worrying a lot about editing. They suit a writer’s flow of words, the need to keep writing and describing without stopping.

Thus, we see a lot of this type of sentence as well. Too much of it. In contemporary novels, public writing, student writing — any type of writing. Both styles can be boring—and, thus, off-putting—to readers.

The Compound Sentence Should Join Two Equal Thoughts

Long the favorite of children who can’t yet rank their thoughts, the compound sentence can go on and on, linked by coordinating conjunctions:

“I saw my friend, and she was going to the store, and I went with her, and I bought some candy, but I didn’t have enough money, but my friend paid for it, and we walked home, and we played a little, but I got hungry, and I went in to eat.”

As endless (and trying) as an evening spent babysitting a restless tot.

But did you know that compound sentences have a specific rhetorical function? Two sentences joined by a coordinating conjunction should be equal in meaning or importance. That’s why a coordinating conjunction, not a subordinating conjunction (although, though, because, when, whereas, if, and more), is used to join two independent clauses in a compound sentence.

Because of ease or just plain laziness or, perhaps, benightedness, the compound sentence style entices many people. For example, “She was hungry, and she wanted to eat lunch.” Clearly, this would be better with a subordinating conjunction — “Because she was hungry, she wanted to eat lunch” — but that would require a little more thinking to discern what the logical connection is. A lot of people don’t take that extra step, but they should.

Polysyndeton can be an effective stylistic choice

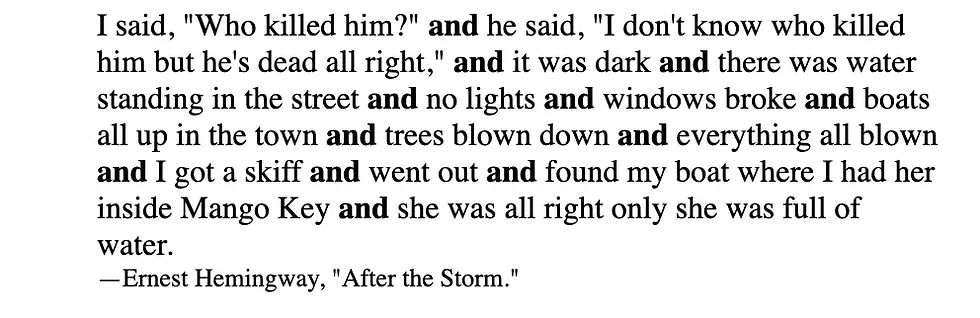

Don't get me wrong. In the hands of a master, the deliberate use of a series of coordinating conjunctions can be effective. It's called polysyndeton, a rhetorical trope. Ernest Hemingway is probably the most famous polysyndeton user. Here's an example from one of his short stories:

Why would Hemingway consciously choose to use coordinating conjunctions in such a way? The narrator of this story is a brute, a lout. In the above excerpt, even murder and death are equal to his boat being filled with water after a storm. Thus, the use of coordinating conjunctions is appropriate in conveying the unrefined nature of the narrator and his rambling, flat narrative recounting. When he comes upon a shipwreck and dives down and spots corpses floating within, he thinks of looting the ship for its gold, not about the people who perished. Polysyndeton equalizes everything.

Martha Kolln’s observations on polysyndeton from her book Rhetorical Grammar remind us of how powerful this device can be: “Polysyndeton puts emphasis on each element of the series with a fairly equal beat.”¹ Each of the sentences in the above excerpt is equal in terms of importance and meaning, relaying the character (or lack thereof) of Hemingway’s narrator. Furthermore, Kolln notes, “Polysyndeton slows us down, perhaps adding a sense of formality.” Hemingway wants us to look at every series within the device and evaluate accordingly.

So when used deliberately and masterfully, polysyndeton can be a powerful stylistic choice. But if used indiscriminately and carelessly, it makes for artless prose.

The loose sentence adds details after a main clause

The loose sentence is defined as one consisting of an independent clause (a stand-alone thought with a subject and a verb) followed by a series of subordinate clauses (a subject and verb preceded by a subordinating conjunction such as although, because, if, when, etc.) and/or descriptive phrases (groups of words lacking both a subject and a verb).

Far too many contemporary writers overuse this sentence structure, adding often inelegant phrases or subordinate clauses. The loose sentence becomes clunky and monotonous when overdone. ( I demonstrate below how a series of these sentences make for an often inelegant paragraph.)

Strunk and White advise writers to "avoid a succession of loose sentences" by surrounding them with a variety of other sentence types.² Good advice.

Used sparingly and artfully, the loose sentence is powerful

Like polysyndeton, the loose sentence can serve up exquisite style if crafted well and mixed in with other sentence styles. This sentence style allows readers to luxuriate in description after the main point at the beginning, allowing for contemplation of the details that follow.

One of my favorite contemporary essayists is Margaret Renkl who writes for the New York Times. Her sentence style and variety encase her thoughts seamlessly. In her essay “Praise Song for the Unloved Animals,” she uses loose sentences to make her readers think about animals often disliked because of their ugliness or lack of appeal. Of the red bat, she writes, “ At nightfall she unfolds her canny wings and skitters to her work, sweeping through the skies, circling under the streetlights, clearing the air of moths whose larvae eat our trees, sweeping up all the whining, stinging creatures we swat at in the dark.”³

Besides precise and descriptive diction that helps us actually see the animal in action, the loose

sentence slows us down so we can appreciate Renkl’s description of the good work this oft-maligned mammal does for the the planet.

The American Scholar editors a few years back chose their 10 “best” sentences, among which can be found a loose sentence or two.⁴ One of these was a sentence from The Great Gatsby that ends in a loose sentence:

That’s how it’s done. No explanation needed. It deserves the slow read its structure requires.

When we edit our writing, we might remember that a variety of sentence styles contributes to an engaging writing style, allowing readers to linger on content, a result of the writer’s fine tuning of not only what is said but how it’s said.

###

(This piece originally appeared in The Writing Cooperative on Medium, July 4, 2023

Photo at top by Pablo Merchán Montes on Unsplash

References

¹Martha Kolln, Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects (4th ed.). Longman. (2003).

²William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White, The Elements of Style (4th ed.). Longman. (2000).

³Margaret Renkl (27 May, 2019), praise song for the unloved animals. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/27/opinion/praise-ugly-unloved-animals.html

⁴Editors, The American Scholar, “Ten Best Sentences.” https://theamericanscholar.org/ten-best-sentences/

Commentaires